Has a Death Occurred? We Are Available 24/7 ![]() (360) 523-2489

(360) 523-2489

![]() Call Us

Call Us ![]() Live Chat

Live Chat

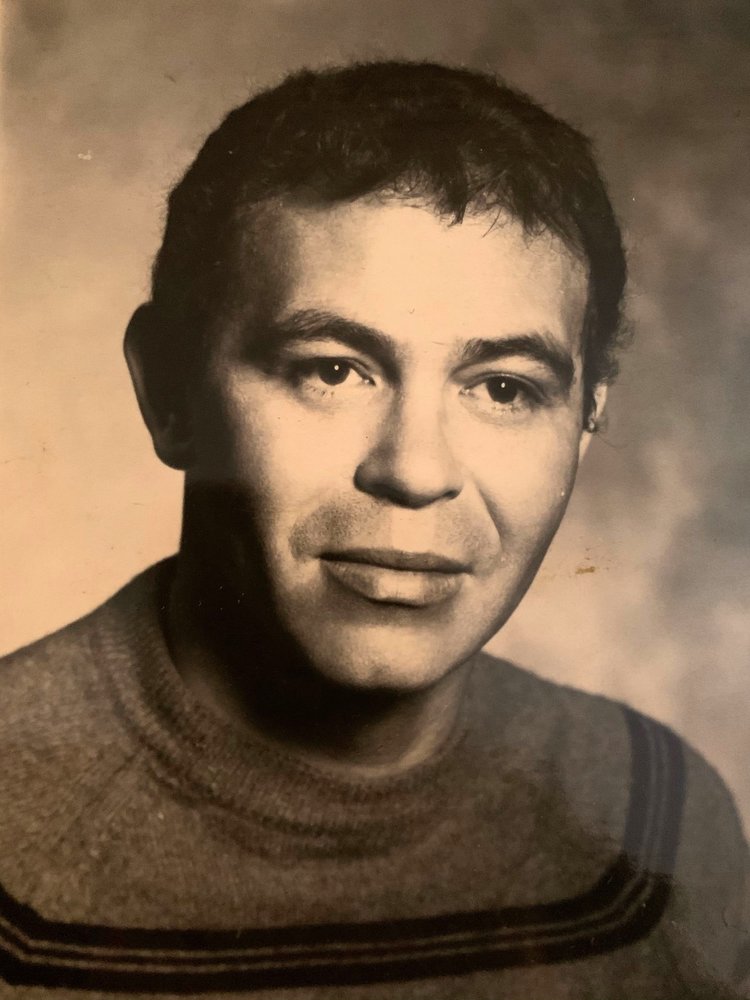

Obituary of Henry Lyle Adams

Henry Lyle “Hank” Adams, age 77, a citizen of the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes, began his Journey to the Spirit World at St. Peter Hospital in Olympia, Washington, on Monday, December 21, 2020, at 14:57 p.m.

Hank was born on May 16, 1943, on the Fort Peck Reservation in Wolf Point, Montana, to Lewis Adams and Jessie Malvaney Adams. Shortly after his birth, his family moved, living in Longview, Washington, and the Dalles, Oregon, and back to Longview before settling in Washington near the Quinault Indian Reservation in Pacific Beach. Hank’s mother, Jessie, had since remarried and moved to Taholah, Washington, for a minister position. She later moved to Queets and served as minister there. Hank attended Moclips (now North Beach) High School, where he played football and basketball, was student body president, and edited both the school newspaper and yearbook. In his first year, he received the coveted Citizenship Award, which was rare for a freshman to receive. He earned the distinction of Valedictorian of his graduating class, with a cumulative 4.0 grade point average.

In adolescence and at the University of Washington, Hank was recruited into treaty rights struggles—against Public Law 83-280 state jurisdiction and Washington’s ban of Indian fishing—by grandchildren of Quinault Treaty Chief Taholah, Jim Jackson and Hannah Mason Saux Bowechop of Neah Bay. In 1962, Quinault Nation President Jim Jackson created his team to work on treaty rights and fish resource management matters: Hank and UW housemate Guy McMinds (Quinault) and Jim Heckman of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service in Olympia. The Quinault leaders had joined Hank into the National Congress of American Indians in 1961 and he later was Research Assistant to NCAI Executive Director Vine Deloria, Jr. (Standing Rock Sioux).

During the famed 1963 March on Washington, Hank teamed up with National Indian Youth Council Executive Secretary Bruce Wilkie (Makah) to bring actor Marlon Brando to Franks Landing on the Nisqually River and into a coalition of 37 Northwest Tribes for a mass public demonstration in Olympia in January to March of 1964. The impetus for the protests had been the fierce defense of treaty rights already being waged by the Nisqually, Puyallup, Muckleshoot and Quileute Tribes, following brutal state assaults on their fishing families dating from January 1962 and the filing of injunctions against them.

This began what would become Hank’s relationship of more than a half-century with the Franks Landing Indian Community matriarch, Maiselle Bridges, and her brother, Billy Frank, Jr., who were his teachers, and he their loyal assistant, advisor and scribe. While initially protesting induction into the armed forces because of the United States’ failure to live up to its treaty obligations, Hank eventually enlisted in the U.S. Army and was stationed for two years at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, where he wrote and edited the Belvoir Castle.

While in the DC metropolitan area, Hank also represented NIYC and led its Washington State Project, with the aid of co-chairs at home, Guy McMinds (Quinault), Sandy Johnson Osawa (Makah) and Leo LeClair (Muckleshoot). He was a key player in the establishment by U.S. Senators Robert F. Kennedy (D-New York) and Paul Fannin (R-Arizona) of the Senate Select Committee on Indian Education, which culminated in the 1969 “A National Tragedy” Report under successor chair, Senator Edward M. Kennedy (D-Massachusetts).

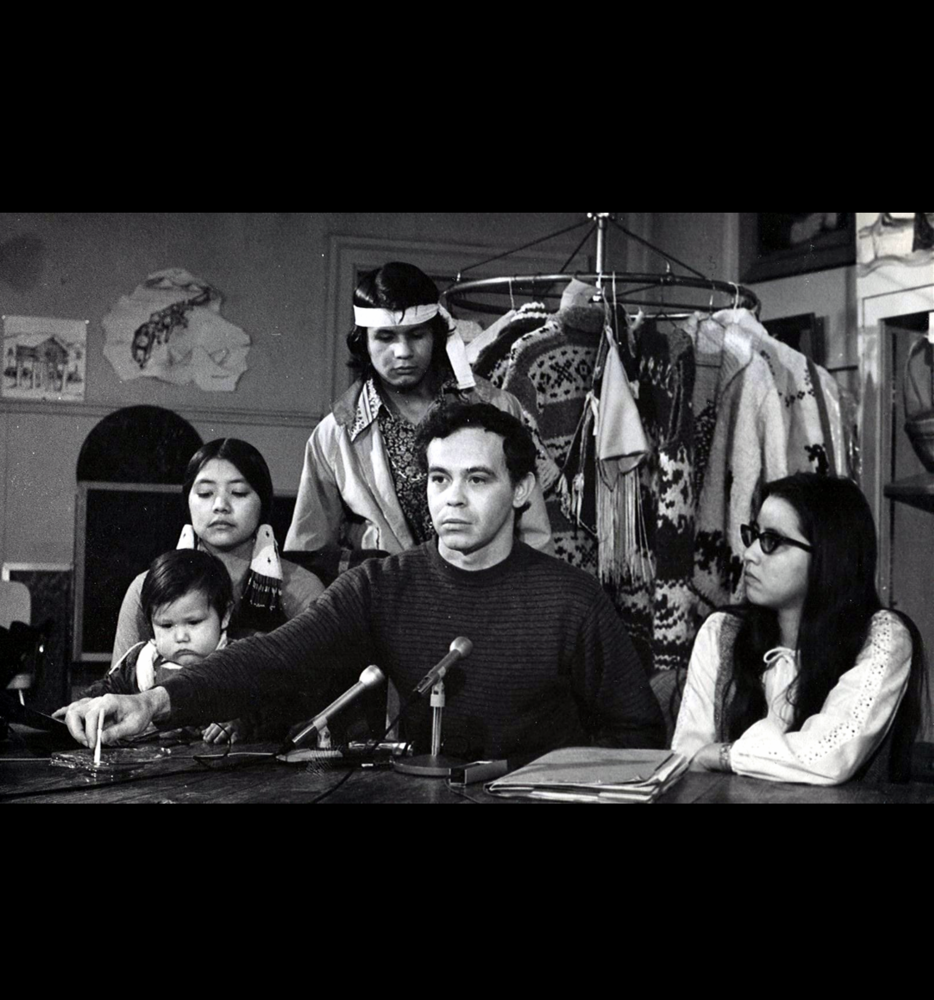

As a civilian in 1967 and director of the Quileute Tribe’s OEO-Community Action Program, Hank was named to the 13-member national steering committee of the Poor Peoples Campaign chaired by The Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968. The Indian activity in the Poor Peoples Campaign—organized primarily by Washington Native people recruited by Maiselle Bridges—drew Hank back to the Pacific Northwest, where he lived out his life as a member of the Franks Landing Indian Community and a resident of Olympia. In 1968, he was elected president of Survival of American Indians Association, founded by others in 1963, and held that position for 52 years.

After furthering his studies at Evergreen State College in Olympia, he was a key strategist, alongside Billy Frank, Jr., during the “treaty-fishing wars” that ultimately led to the 1974 Boldt Decision and the 1979 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that upheld it. U.S. District Judge George H. Boldt uniquely admitted Hank as lay counsel into the case of United States v. Washington, specifically to represent Billy Frank, Jr., and Reggie Wells and other Nisqually treaty fishermen on various issues. The landmark ruling affirmed tribal rights under 1854-56 Treaties, to 50% of the harvestable catch of salmon and sturgeon (later cases in the Boldt line affirmed rights to shellfish and habitat restoration, including dam removal), in usual and accustomed places, on- and off-reservation, for ceremonial, commercial and subsistence purposes.

It has been said that, without Hank Adams, there would be no U.S. v. Washington. Hank’s passion to protect American Indian Treaty rights would drive his activism throughout his life and lead to injuries and a few stays in jail, where he continued to pursue his self-taught legal education. He was tapped by the U.S. Congress in 1975-1977 to chair its Task Force One on Treaties & Trust Responsibilities of the U.S. House-Senate American Indian Policy Review Commission. He served with Native American Rights Fund staff attorneys John E. Echohawk (Pawnee) and Douglas R. Nash (Nez Perce). Today, Echohawk is in his fifth decade as NARF Director, and Nash, after a long career in tribal and private practice, is Director of the Center for Indian Law and Policy at Seattle University School of Law.

Hank’s work has been recognized with an Abraham Lincoln Human Rights Award by the 3-million member National Education Association in Detroit (1971); State and National Jefferson Awards in Seattle and at the U.S. Supreme Court (1981); and the third American Indian Visionary Award presented by Indian Country Today at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. (2006), following first ICT Visionary Award honoree Billy Frank, Jr., in 2004 and the second, Vine Deloria, Jr., in 2005. Ever generous in accepting accolades, Hank noted he would have placed Maiselle Bridges, Ramona Bennett (Puyallup), Tillie Walker (Mandan-Hidatsa-Arikara) and Suzan Harjo (Cheyenne and Hodulgee Muscogee) before his name in making that award.

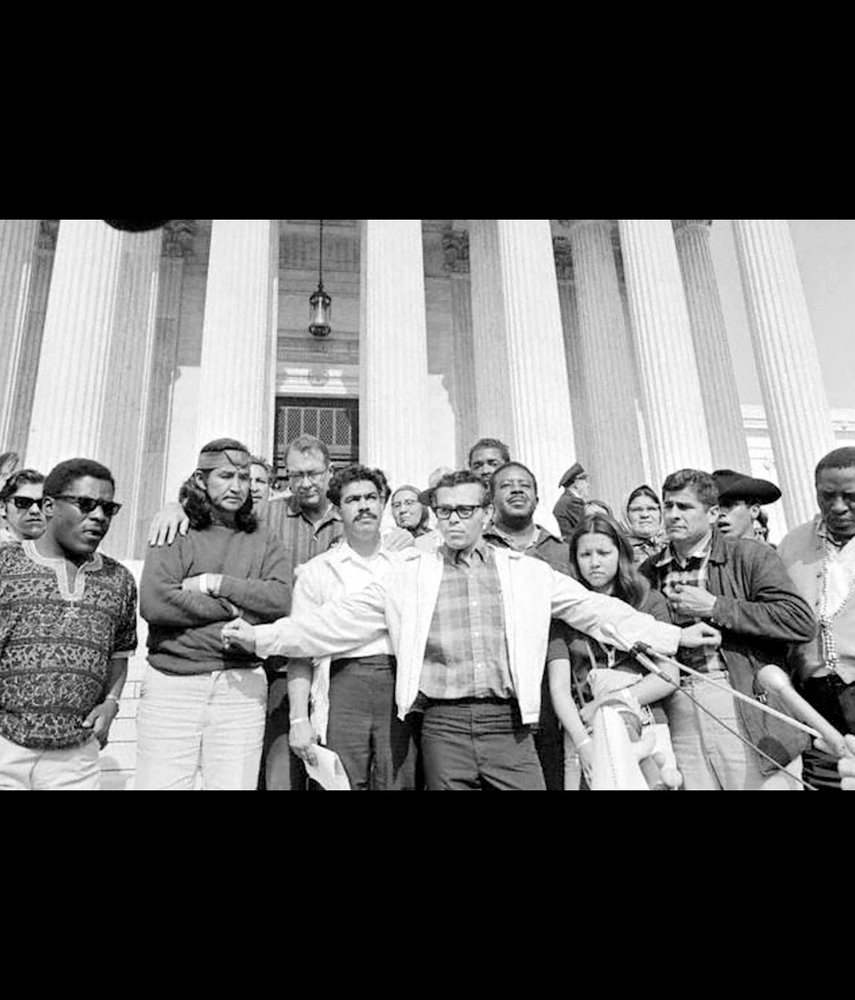

Of all his accomplishments, Hank is perhaps best known for his authorship of the 1972 Twenty Points to petition the federal government to address Indian needs and conditions that resulted from broken treaties. Copies of the Twenty Points were driven to Washington, DC, by American Indian people from hundreds of Native Nations in late-October, days before the national election. Weary from the long Trail of Broken Treaties and frustrated by the less than warm welcome, AIM leader Dennis J. Banks (Leech Lake Ojibwe) said, “The Bureau of Indian Affairs employees went home and we stayed in the building.”

Both the White House liaisons and TBT leaders trusted Hank to negotiate an end to the six-day takeover and the peaceful exit out of DC. Hank also negotiated the return of BIA documents to the White House, after an opportunity to read them, but he and investigative reporter Les Whitten were arrested for possession of the papers as they were returning them. Grand jurors laughed at the absurdity of the arrests and declined to indict the pair. Eight years after authorities charged him with possessing stolen BIA documents, Adams’ Jefferson Award was made by a foundation dedicated to promoting public service activism.

At age 29, Hank had “crafted a manifesto a professor of American Indian studies called one of the most comprehensive indigenous policy proposals ever devised. Adams’ “20 Points” which became the formal proposal submitted to the Nixon administration in November 1972. The document is still celebrated in Indian Country today.” (Hank Adams – An Uncommon Life, published by Legacy Washington).

Hank was credited among others for the eventual resolution of the 1973 occupation at Wounded Knee on the Oglala Sioux Tribe’s Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota. He remained engaged in ongoing legal fishing battles in the Great Lakes and elsewhere, and arranged an undercover visit to determine the well-being of the Miskito People in Nicaragua during the Sandinista/Contra conflict that was occurring in the heart of Miskito Indians’ territory.

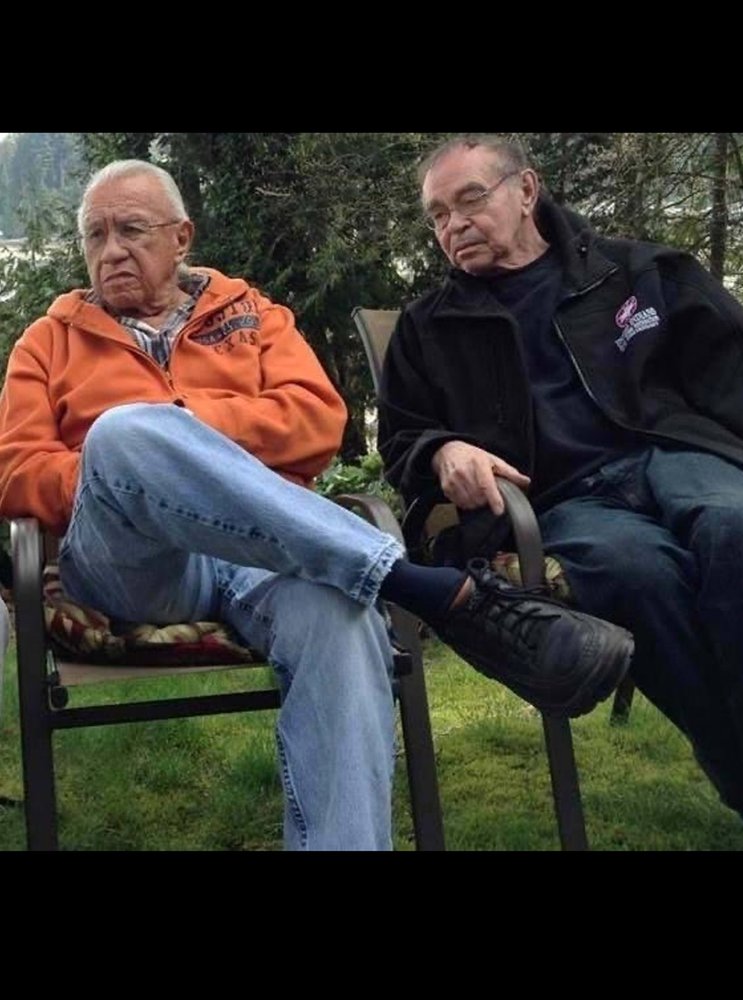

Instrumental in the development of the Wa He Lut Indian School at Franks Landing, he also was a founding member of the Northwest Indian Fish Commission. For his life work, the Northwest Indian College, established by the Lummi Nation, awarded him an Honorary Doctorate of Humanities in Native Leadership.

Words cannot adequately describe the impacts resulting from the visionary work of Hank Adams from the 1960s to the present. Many of our Native people hold a small piece of that history. Most of us have benefited from it. And perhaps only a few with first-hand knowledge are still here to tell the stories.

According to his family, Hank was an eccentric and beloved brother and uncle. He was the family member who showed up unexpectedly to his nieces’ and nephews’ state championship games, school plays, weddings, and special events. At those events, he’d be sure to capture the important moments through photographs and video clips. A “short visit” to his home rolled into hours listening intently to Hank’s latest projects and trips and feeling honored to have spent those hours with him. In each of the Indian reservations where he resided, people often said that he knew more about family members, family trees and their history than the families did. He had commented at one point that his passion for his work was for his nieces and nephews, and for Indian families throughout Indian Country.

Hank Adams is survived by his sisters, Lois Adams Charley (Taholah, Washington), Martha McBride Stout (Taholah, Washington), Sarah McBride (Tumwater, Washington), and Alice Marie Smith (Neillsville, Wisconsin); his brothers, William “Bill” Adams (Taholah, Washington), Tom McBride (Humptulips, Washington), and George Cole (Taholah, Washington); and numerous nieces, nephews, great nieces, great nephews, and cousins. A special mention is made of his close cousins, Rosemary Adams and John Clark, and his godson, Brandon.

Hank is preceded in death by his father, Lewis Adams; mother, Jessie Malvaney McBride; uncles, Phil Malvaney, Jiggs Adams, Charles Adams, Matt Adams and Leonard Hubbard; aunts, Mary Clark and Cora Adams Mount; sisters, Alice Rose Adams, Beverly Linderman and Charlene McBride; and brothers, Walter Adams, Jim Adams, Sr. and Jerry Hyasman; niece, Alice Rose Adams; nephews, Marcus McCrory, Mike Fransen, Darryl Clark, and Wambideezi Adams; cousins, Delilah Hubbard, Ruby Clark, Marilyn Adams; and other cousins and relatives.

In accordance with Hank’s wishes, he will be cremated and his ashes released on the Missouri, Nisqually, Quinault and Columbia Rivers, at such places and times that the family can safely release the ashes.

True to his humble nature, our beloved Hank Adams agreed to an honoring dinner provided that fellow activist, the late-Billy Frank, Jr., and other close comrades also are recognized. Therefore, within the next year, his family and close friends will plan a memorial dinner that he envisioned.

Please leave condolences or share memories and photos on the Tribute Wall to the left.

To send flowers to the family or plant a tree in memory of Henry Adams, please visit Tribute Store

Copyright © 2022 | Terms of use & privacy Policy